This is the first part of what will be a 10–part series of blog posts, which will ultimately be published in full as a single report. Two parts will be published each week for the coming weeks.

Once upon a time…

In late 2016, EY, the professional services firm, published a report on large power sector projects and how well they were being built (Spotlight on power and utility megaprojects — formulas for success).

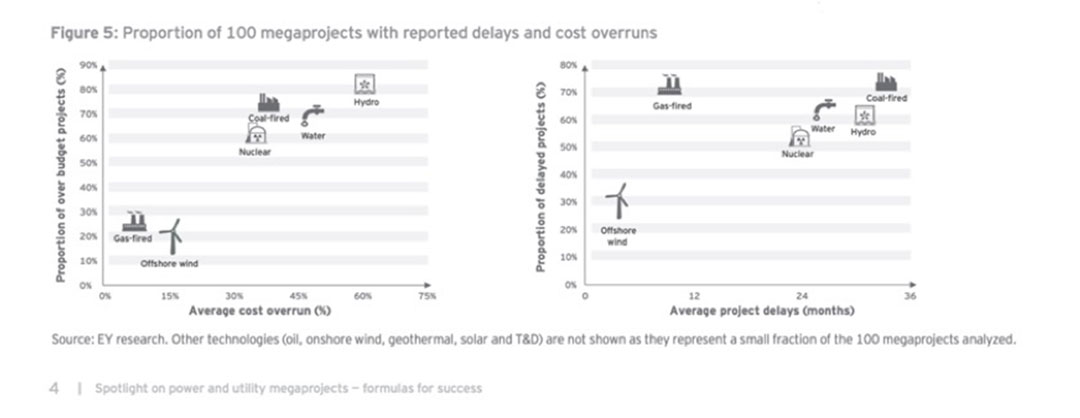

Figure 1: Cost overruns and delays in power sector mega–projects. Source: EY)

Unsurprisingly, it noted that most of these very large projects suffered from cost overruns and delays, sometimes on a quite massive scale. However, what stood out was how much better offshore wind projects seemed to be faring, with the lowest delays and cost overruns by far, despite being a relatively new and immature sector, and despite the obvious intrinsic difficulty of installing large industrial facilities in a very hostile and inaccessible location – the open sea.

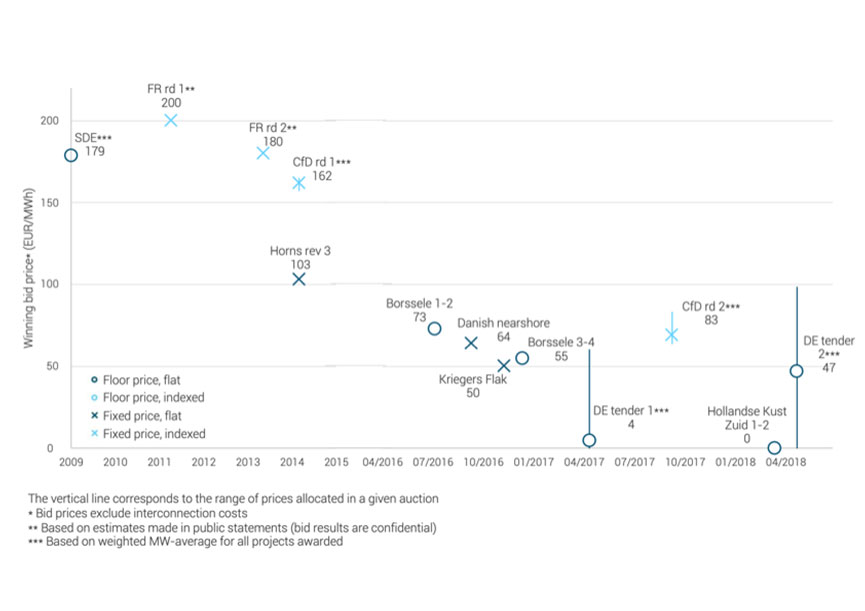

Not long after that, Ørsted, the Danish utility that was one of the pioneers in offshore wind and still is the market leader, stunned the world with a bid to build the Borssele 1–2 project in the Netherlands for a record low tariff of 72.7 EUR/MWh, at a time when most countries were still offering feed–in tariffs around 150 EUR/MWh for offshore wind projects. A few months later, the next Dutch project, Borssele 3–4 was awarded at the even lower tariff of 54.5 EUR/MWh to a consortium led by contractors Van Oord and MHI Vestas, and the Danish nearshore tender was won by Vattenfall with a tariff of 49 EUR/MWh. And soon afterwards Germany awarded the first “zero–bid” project, where the sponsors effectively saying they could build projects on the basis of ongoing market prices, without any medium term revenue stabilisation mechanism. An industry that had until then required substantial subsidies to get projects built was suddenly confident that it was fully competitive against all other power generation technologies and could provide cheaper electricity than the market.

Figure 2: Offshore wind tender prices, 2009–2018 (Source: Green Giraffe)

This document will discuss how the industry managed this feat, and the prominent role that project finance lenders, a rare breed of financiers, played in that success. This paper thus tells the story of how early projects were financed, what was learnt along the way, and what this means for today’s projects. In particular, this will underline how financial engineering was critical in (i) getting a lot of things right during the early generation projects and (ii) bringing the net cost of electricity (the “LCOE” – levelized cost of electricity) down.

Stuff happens

And yet, the early days were not straightforward…

![A collapsed crane in the [Ijmuiden] port](https://wfo-global.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/03-2.jpg)

Figure 3: A collapsed crane in the [Ijmuiden] port

In the summer of 2007, an accident took place on the quayside of the Ijmuiden port. The crane on an offshore installation barge fell down on the quay and crashed. Thankfully, nobody was seriously injured and there was only limited damage to the wind turbine components; however, the crane itself could not be repaired anymore.

That obviously made the installation barge inoperative and prevented for some time the transport of wind turbine nacelles from the quay to the “Q7” offshore site at sea where a 60-turbine, 120 MW offshore wind farm was under construction in Dutch water. The accident took place in July, precisely the period when the weather is calmer and it is much easier to do construction work at sea.

Just a year later, in July 2008, another project, the 6-turbine, 30 MW C-Power phase 1 in Belgium, reported an incident: while pouring sand into the concrete foundations at sea, the plastic “J-Tube” that was supposed to house the cable connecting the turbine to the rest of the project was crushed by the pressure. Quickly identified as a design error (the plastic used for the tube was strong enough for water but not for packed sand), the incident threatened to prevent the connection of the project’s turbines to the grid altogether.

The Q7 wind farm (also known as the “Prinses Amalia” wind farm) and the C-Power phase 1 project being the first two offshore wind project to be financed by banks on a non-recourse basis (respectively in October 2006 and May 2007), this in each case became an immediate and severe test of whether their financial structures were sturdy enough to resist to such events, and whether the industry could hope to continue to be financed using “project finance”.

Other early offshore wind projects also had to face severe problems during construction or early operations, such as Horns Rev (serial defects on the gearboxes leading to their eventual full replacement at sea), Greater Gabbard (flaws in the welding of the foundations, leading to delays in their production and the installation of the turbines), but as these were built on balance sheet, the problems were kept between the project owner(s) and the contractors, and much less public or semi–public information was made available about them.

Side note – offshore wind has been tough for for oil & gas contractors

For oil & gas contractors, the temptation to get involved in the nascent offshore wind sector was strong – no obvious competitors from the wind industry side with experience working at sea, familiarity and experience with the main area where projects are built (the North Sea), attractive size of contracts. And indeed players like KBR, Fluor, Bechtel and Technip, who have long experience offering “EPC” (engineering, procurement, construction”) contracts in the oil & gas sector, tried to get involved. Unfortunately, it quickly appeared that offshore wind was quite different from offshore oil & gas – serial construction rather than large bespoke structures, a capped revenue structure that means that cost discipline is a lot more important than simply getting things done (in oil & gas, the cashflows from a producing well are such that it is almost always worth it to spend more to get things done faster; in offshore wind, this is not the case), and the technical features of the turbines themselves, requiring specific design and installation for each individual generator. The early attempts by oil & gas contractors to build offshore wind farms (KBR on the Barrow project (UK, 90 MW), Fluor with Greater Gabbard (UK, 504 MW)) were therefore quite challenging, leading to losses and/or long disputes with project owners or subcontractors. As a result, most of the large oil & gas contractors quit the market in the early 2010s, or focused on very specialised tasks (like cable installation) and the marine construction work ended up being dominated by another breed of offshore contractors: the dredgers, lead by DEME and Van Oord.

Dealing with problems

In the end, both Q7 and C–Power were built within the timetable and funding the banks had allocated for in their pessimistic scenarios, thanks to massive efforts by the project teams to resolve the unexpected problem:

- For Q7, construction work was delayed by several months. A temporary solution was found by using a mobile crane on the installation barge, but that was less efficient and slower and it was already autumn by then. This meant being able to work fewer days of work each month as weather conditions became more difficult, and increasing delays. Thankfully, as no work had originally been scheduled at all during these harsher winter months, the project was able to slowly catch up on its original schedule.

- For C-Power, the project team, with the help of contractor DEME, quickly designed an external steel “robe” to be installed on the outside of the foundation to carry the cable that could no longer be pulled through the J‑Tube inside the foundation. The team managed to design, manufacture and install this within a few months, allowing the consequences of the accident to be mitigated. The cost of that effort was fully borne by insurance – the insurers were quickly convinced by the solution proposed by the project and saw it as a much cheaper alternative than waiting and litigating as they were clearly on the hook in any case for the loss of production that would have happened otherwise.

Figure 4: Installing the external “robe” on a C–Power foundations (Source: Giants on the Thornton Bank, Jan Strubbe)

These two incidents confirmed what had been a core assumption of the banks funding the projects: problems will inevitably happen in such projects, what mattered most was the ability by the project to withstand the consequences and solve them. That meant, in practice, having (i) enough time and funding buffers to be able to deal with the unexpected, and (ii) the right people to actually understand issues, identify solutions and implement them.

Now that the offshore wind industry has moved to another dimension, it is important to remember these principles, as they still underpin the fundamental philosophy of how projects are built, and how they are financed.