ENVIRONMENTAL STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT DEFINITION AND TOOLS

Environmental stakeholder engagement is a process used to influence the acceptability of offshore wind projects among groups directly affected by them. Successful environmental stakeholder engagement facilitates the permitting process and ultimately reduces the potential negative impacts of a wind farm throughout its lifetime.

The engagement process is contingent on a region’s regulatory framework for offshore wind. Differing socio-economic characteristics also mean that different stakeholders play a role in each context. However, there are common tools and strategies that can be used to create an effective process that is accessible, transparent, and more community based. In considering the power dynamics between stakeholders, these measures can also help foster trust and fairness of outcomes.

Start the engagement early

The offshore wind project planning process (or development phase) is the most appropriate time to receive mutually beneficial ideas for sharing space and prevent future conflicts. In its best practice guideline, the Fishing Liaison with Offshore Wind and Wet Renewables Group (FLOWW) underlines the effectiveness of constructive engagement prior to and during the environmental impact assessment process. Similarly, a workshop organised by the ORE Catapult highlighted the importance of stakeholder consultations before the project site is selected.

For example, following two public consultation events with the local community and other stakeholders, the Pentland Floating Offshore Wind Farm (in the development phase) decided to reduce the originally planned offshore wind site area for the turbines by 50% and reduce the number of turbines in the design envelope from ten to seven. Now, the project is continuing environmental impact studies as part of the permitting process in Scotland.

Once the framework for communication and feedback is established during the development phase, engagement is expected to continue throughout the installation, operation and decommissioning phases of the project so that mitigation measures are continuously adopted. Taking the same example of the Pentland project, there will be an opportunity for the public to comment on the project’s final application for consent, with anticipated communication activities to be carried out at the later construction, installation and operation & maintenance (O&M) phases.

Create an engagement framework with feedback loops

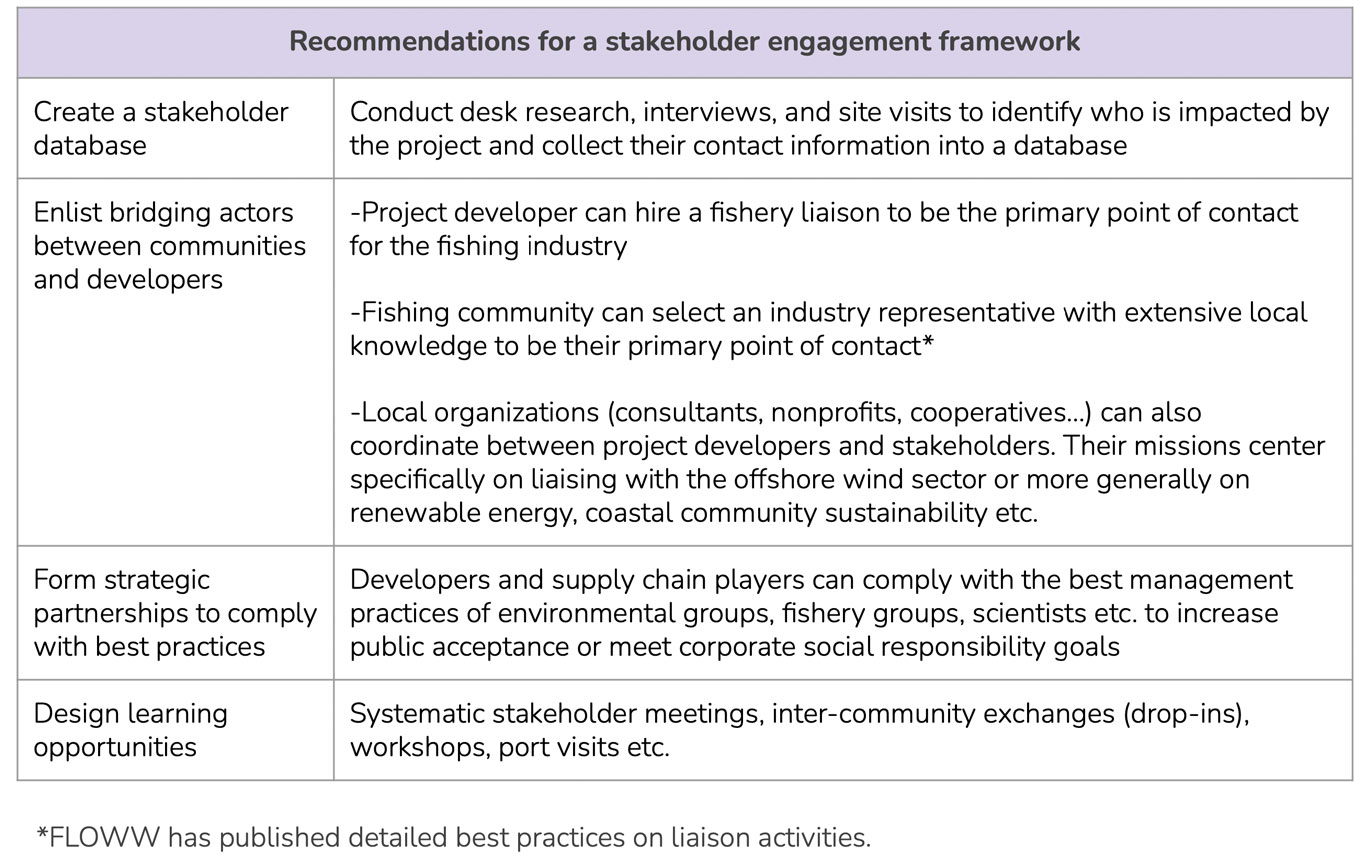

The below table summarises elements of an engagement framework at the project level. However, strategic partnerships can expand into international exchanges where organisations and/or governments of one country share best practices with their counterparts of another country. Bridging organisations notably help shape these lessons learned by creating unified stances among stakeholder groups.

Sources: WFO, Equinor (2018), FLOWW (2014), Klain et al. (2015), NRDC (2019), Hall & Lazarus (2015)

Major offshore wind developers hire fishery liaisons to ensure the flow of information and maintain discussion with the fishing industries. Inversely, it is enormously helpful to the project developer to also work with a single point of contact within the local fishing community who “can be trusted to represent an unbiased fishing industry view of the region”. In the United Kingdom, developers provide details of these roles when applying for consent to develop a specific project: Ørsted’s Outline Fisheries Coexistence and Liaison Plan for Hornsea Project Four, March 2022.

The specific approach to meeting stakeholder groups is also important for the information gathering process and ultimately reaching consensus for future decisions. In the case of the Fécamp offshore wind project under construction off the coast of Normandie, the developer met with stakeholder groups separately before setting up a local committee comprising all groups to decide the final project zone.

Make information readily available and accessible

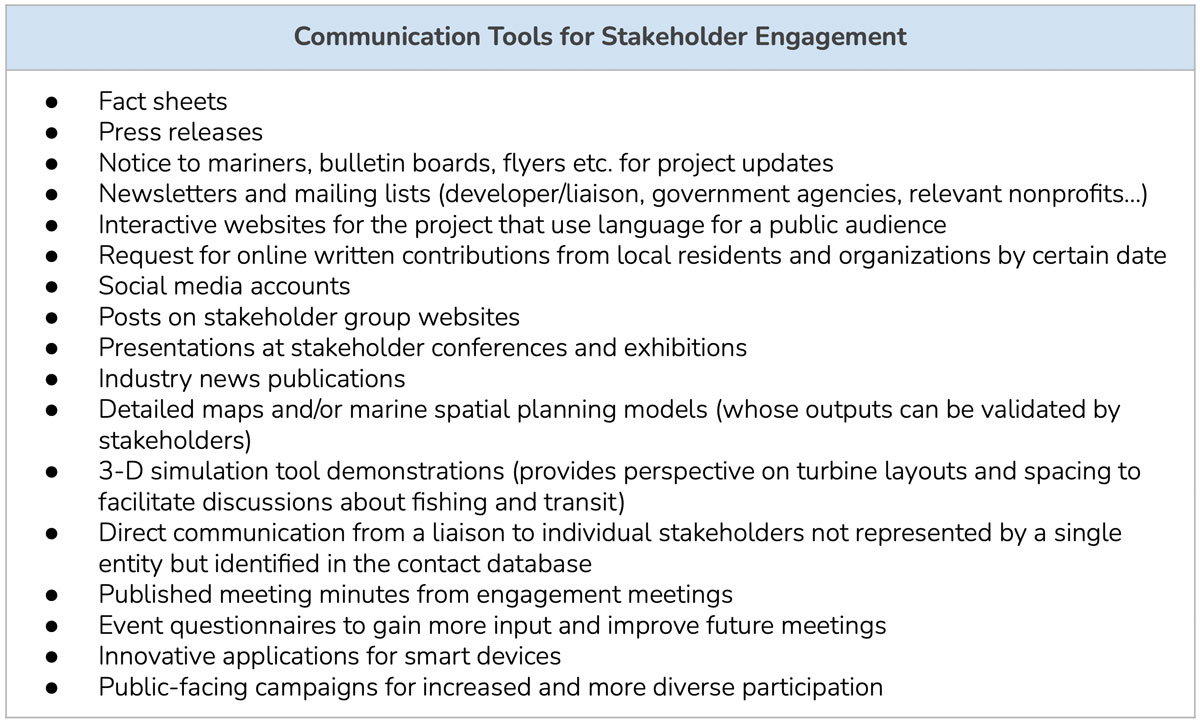

Below is a list of communication tools used throughout the engagement process. A communication schedule is important for relaying time-sensitive information like meeting invitations, feedback solicitation and/or warning of incoming surveys, installation and O&M activities.

Sources: WFO research, Klain et al. 2015, Equinor (2019), Equinor (2018), NYSERDA (2017), FLOWW (2014), Lester et al. (2018), Díaz (2020), EFGL website, Groix & Belle-Île website, Statoil (2015), Pentland Floating Offshore Wind Project website

When engaging with the public, representatives should be ready to explain concepts in simplified language. Creative methods can help explore more complex topics: Keijser et al. (2018) developed a board game to facilitate learning on maritime spatial planning during a workshop. Outside of the project development process, educational initiatives across local schools and colleges (the case of the EFGL project) or even tourism activities (although results can be more nuanced) can help increase the public understanding of the project but also more generally offshore wind technology.

Goals of stakeholder engagement

Below are three main outcomes of the stakeholder engagement process. Please note that they are not meant to be understood as separate pathways. Rather, a combination of outcomes is often achieved in real life.

Mitigation

Engaging with stakeholders early helps identify all of the potential impacts of an offshore wind project. The developer can then devise a plan to mitigate them. As such, it is important for the developer to remain flexible throughout the project. Some examples of mitigation practices include:

- Siting a project away from breeding grounds

- Using quieter foundation types

- Time construction periods to avoid overlap with migratory patterns

- Reducing vessel speeds

- Increasing distance between turbines

- Arranging the turbines into lines rather than squares to free up fishing space

- Aligning rows of turbines along a consistent water depth since mobile fishing gear is often towed along a consistent depth

Joint achievements such as defining the final project area, position of floating lidars and common processes for carrying out studies (e.g. geophysical) are ideal results of the mitigation pathway (e.g. Groix & Belle-Île project).

Co-existence

Rather than working “within constraints” of the ocean environment, this outcome identifies opportunities for offshore wind to work with other marine industries and/or create community benefits. Examples of co-existence include:

- Collecting and sharing ocean data with fisheries

- Using the floating wind farm to support artificial reefs; marine protected areas; alternative fishing gears (e.g. Fukushima FORWARD; Hywind Scotland)

- Co-locating the wind farm with leisure; tourism; aquaculture activities; wave/tidal energy

- Sharing generated electricity for local users at a subsidised rate

- Creating local content and other economic benefits by hiring fishing vessels to service the construction and maintenance of the farm; providing local investment opportunities during the project (e.g. crowdfunding campaign for the EFGL project); using wind farm profits to fund fishery monitoring; creating a community benefit fund for the project (e.g. Pentland project)

Increasing interest in the concept of co-existence is illustrated by the Multi-Use in European Seas (MUSES) project that explored “multi-use” in European seas, which is the “intentional joint use of resources in geographic proximity”. However, this term has yet to be more explicitly mentioned at national and municipal levels of governance.

Compensation

When negative impacts are unavoidable, the developer can provide financial compensation to support those who will lose from the project. This could take the form of a direct financial compensation to a stakeholder group (the case of WindFloat Atlantic in Portugal) or through legal instruments like community benefit agreements (the case of South Fork in the U.S.). A community benefit agreement can also focus more on creating local content like in the case of Vineyard Wind in the U.S.

As explicitly noted in Equinor’s 2019 Fisheries Mitigation Plan for the Empire Wind Project, resorting to monetary benefits should be considered only if mitigation and co-existence options are deemed insufficient or unfeasible. This is mainly because quantifying and distributing the compensation can be difficult, external funding opportunities may be difficult to mobilise, and community benefit agreements risk being perceived as bribes for consent.

In areas where it would be difficult to transfer the experience of stakeholder groups to work on offshore wind farms (e.g. the case of small fishermen households with low levels of education in Taiwan), compensation becomes an important tool.

Necessary efforts to secure long-term, effective stakeholder relationship

Decision-making for multi-use of maritime resources should be based on the most up-to-date and accurate science. However, there is a lack of baseline data on the ocean environment. Strategic partnerships like mentioned earlier can help coordinate research and monitoring efforts of offshore wind impacts at various spatial scales. For example, developer Ørsted worked with the Holderness Fishing Industry on a long-term study examining the effects of offshore wind construction activities on shellfish populations. The study was a first of its kind and concluded that there were no significant negative impacts on the ecology of the European lobsters.

Working with different stakeholders and collecting their input can also facilitate the use of innovative approaches like marine spatial planning models and technologies to improve ocean knowledge (e.g. remote sensing, AUVs/ROVs, lidar, turbine-mounted cameras for analysing bird behavior, innovative monopile designs that allow marine life to swim through or grow inside the foundation). Lastly, making data from environmental studies publicly available is important to maintain transparency and access to information, i.e. by uploading the files directly onto the project websites.

In areas where offshore wind is very new, offshore wind players can work with a negatively skewed assessment of public attitudes that hinders project development. This is because the conversation on public acceptability is still limited to the most impacted stakeholders. Assessing support in various communities is thus an important part of the stakeholder engagement process and could help change the general opinion.

EXPERT INSIGHTS FOR FLOATING OFFSHORE WIND

Floating offshore wind is a relatively new technology with unique pros and cons compared to bottom-fixed offshore wind. WFO conducted 7 interviews on the topic of environmental stakeholder management for floating offshore wind to get a better sense of project impact mitigation and co-existence opportunities.

Stakeholder engagement approaches

All of the interviewees (7/7) mentioned the importance of engaging early. One interviewee mentioned France’s public debate process (débat public) as a good example of early and organised engagement. France’s process notably allows stakeholders to contribute to the siting decision. By contrast, two interviewees described U.S. regulatory agencies (in particular BOEM) as having issues with communication, accountability and trust. Two respondents mentioned stakeholder representatives (liaisons) as a good way to keep local interests at the forefront of the conversation.

Overall, stakeholder engagement is viewed as a collaborative effort between project developers and regulatory authorities. Two interviewees (2/7) specified that the developers should ultimately lead the process. Two representing the supply chain noted that their role on this topic is limited to providing technical transparency on their products and services. For them, having a framework in which they can explain their work to concerned groups is a priority. However, three respondents (3/7) mentioned that the onus of engagement should not be entirely on the developer; regulatory agencies must assist with stakeholder coordination and environmental data collection. Additionally, two respondents highlighted the power of regulators in prescribing engagement expectations early into the industry’s regulatory framework.

Two respondents (2/7) highlighted the relevance of international collaboration for improving stakeholder management in floating wind. One organisation mentioned their work with an international environmental non-profit on environmental impacts. Another alluded to Denmark’s sharing of lessons learned with Asian governments by flying out Danish fishermen to talk to South Korean fishermen about the impacts of offshore wind. The UK has also sent British fishermen to the US to discuss their experience.

Goals of stakeholder engagement

Overall, interviewees thought positively of the potential for co-existence between floating offshore wind farms, marine protected areas, aquaculture, other marine renewable energy sources etc. When placing floating wind farms on top of ecologically important areas, one supply chain player mentioned the importance of early communication as floating offshore wind facilities are affected by microbial corrosion (e.g. use of synthetic ropes for mooring lines). Another supply chain respondent questioned the impact and ethics surrounding decommissioning a project once an ecosystem has adapted itself to the structures. Lastly, one respondent specified that co-location would only work if strong coordination between involved parties is established. For instance, should an issue arise, who would be accountable for it?

Two respondents (2/7) went into detail on creating local content as a form of co-existence. Where local port infrastructure is of particular importance, floating offshore wind projects can provide opportunities in construction, installation and O&M. However, further investments are required if a community would want to benefit from manufacturing work (especially when production capacity is not present). Opinions on the potential for hiring fishing vessels to service the projects and collect environmental data were mixed.

One respondent underlined that compensation mechanisms, while common practice, would be concluded after first assessing mitigation options.

Two respondents (2/7) brought up the trade-off of scaling up quickly vs. investing to create local content and reduce carbon footprint (i.e. being more sustainable). Countries who could have high potential of local content may outsource the work for a project instead because of lower costs. Manufacturing hubs would ideally exist in multiple locations across the planet in order to capture economic benefits and reduce environmental impacts. One respondent suggested making environmental sustainability a statement of purpose for offshore wind projects.

Necessary efforts to secure long-term effective stakeholder relationship

Three interviewees (3/7) were explicit on engaging more with data for site investigation. One respondent specifically suggested that building a template of data needs could help obtain key information in advance of an offshore wind project. Another participant is developing an innovative application to facilitate the data gathering and sharing process between stakeholders. This individual had seen first-hand how stakeholders can each have their own claims on the marine environment, thereby impeding consensus. Experience with stakeholder management in offshore wind has revealed a general need to better understand the ocean environment for future marine spatial planning approaches.

Two interviewees (2/7) mentioned the need to better communicate the pros and cons of floating offshore wind to the public. There are many unique pros to floating offshore wind, but there has yet to be a clearer picture on where the technology fits in the marine renewable energy space. Public-facing campaigns can also include more people in the conversation and ultimately enhance acceptability.

CONCLUSION

Successful environmental stakeholder engagement can help secure the socio-economic and environmental benefits of offshore wind (bottom-fixed and floating). Moreover, a solid engagement framework can reduce the financial risks associated with project delays, litigation and permitting issues.

For floating offshore wind specifically, it will be important to balance sustainable engagement practices and outcomes with cost reduction opportunities as the industry transitions to commercial scale. Lessons from existing engagement processes reveal the larger need for floating wind to secure its place as a viable marine renewable energy technology. Studying and communicating what floating offshore wind would look like in specific locations can enhance the understanding and acceptability by critical stakeholders.