This is the fifth part of what will be a 10–part series of blog posts, which will ultimately be published in full as a single report. Two parts will be published each week for the coming weeks.

Earlier instalments:

Investing in offshore wind

Project development cycle

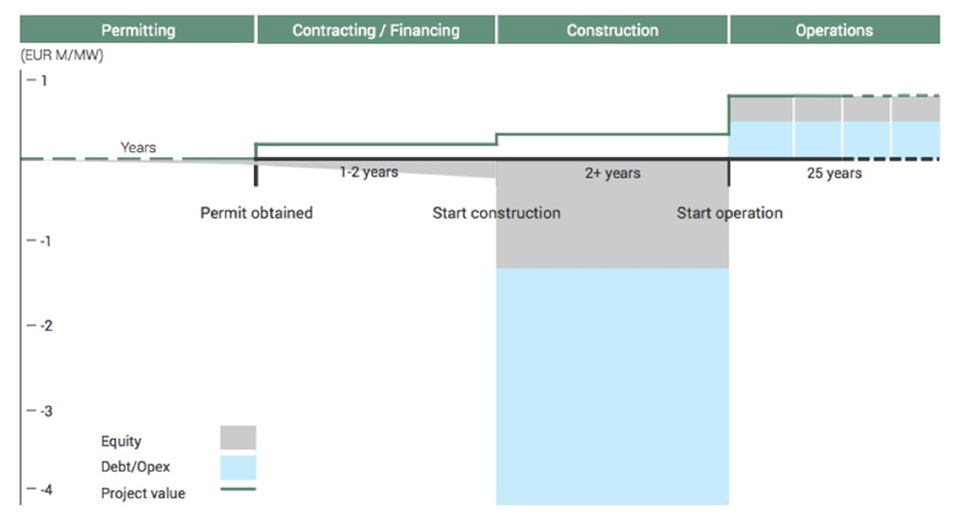

Like all large infrastructure and power projects, the development of an offshore wind farm (OWF) includes several phases which are worth describing in detail to identify the important milestones. These milestones correspond to increases in a project’s value.

The broader phases in the life of a project are:

- Early development (site identification and control, permits)

- Late development (contract negotiations, financing);

- Construction (installation of foundations, turbines, internal cabling, grid connection); and

- Operations (power is generated, the facilities are operated and maintained over 25 years or more)

Figure – project development cycle

Source: Green Giraffe. “Recent trends in offshore wind finance”, April 2019, S11

The two first phases are often called the “development phase”, with the project moving to construction when FC or FID is reached.

Early development phase: permitting

This phase requires relatively little capital but is time-consuming – typically taking several years. For an OWF, it requires obtaining the following:

- site control – the right to exclusive use of a defined area at sea (or in a lake), including the right to put an offshore wind farm on that location;

- permits – the full suite of permits making it possible to build and operate an OWF. This will include a license to operate, the relevant construction permits, environmental reviews and may include more specific requirements in certain locations (approval by military authorities, shipping authorities, fisheries, certification of the proposed design, etc.) as well as the permits required for onshore works (usually the cable landing and connection to the main grid). These permits can only be considered as final or in place when they are no longer subject to any potential appeals process;

- revenue regime – access to some form of price support under the relevant regulatory framework that makes offshore wind economical on such site. This can take the form of a feed-in tariff, a contract for difference, a long term fixed price power purchase agreement with the local utility or another party or “green certificates”/ renewable obligations. The revenue regime allows a project to be economical given the upfront investment costs and the need to finance or amortise such up-front investment over a long enough period to make the average cost of electricity over the period low enough. For OWF projects, such price support will ideally take the form of a long-term regime which provides pricing visibility over 10 to 20 years; at the very least, the project should have the right to sell production on the wholesale market and get access to the spot price; and

- grid access – access to the high voltage grid, whether at the project’s location or at an onshore sub-station. Such grid connection may need to be built by the project or by the grid operator and may be subject to a parallel permitting process.

A project with all 4 items above is usually described as “fully permitted.”

A project usually does not start the contracting and financing phase without being fully permitted or having sufficient comfort that it can achieve that status in a predictable timeframe. The reason is that the above four items are substantially driving the nature and main features of an offshore wind project (such as number of turbines, tip height, maximum generation capacity, siting constraints, etc.) , upon which the contracting and financing structures rely.

The cost to get to a fully permitted project would typically be 0.05–0.1 MEUR/MW, i.e. in the order of EUR 50‑100 M assuming a 1,000 MW nameplate capacity. A substantial part of this cost is linked to environmental studies and the geotechnical and geophysical studies, which are required to understand seabed conditions in order to identify the exact locations for the foundations for the wind turbines and finalise their detailed design. Timing can go from a few years to many years, depending on how settled the permitting process is and whether there is any legal action against the project. And of course, the numbers above represent a “best in class” level for projects with experienced developers.

- Main risks

- Delay to permits, or failure to obtain them all;

- Changes in regulatory framework that make the project unviable.

- Timing and funding required

- Several years;

- EUR 50‑100 M for a ca. 1,000 MW project.

Late development phase: contracting and financing

A fully permitted project is not yet ready to be built. In what is traditionally called the “late development phase”, the developer must set up the full contractual and financial package to actually build the project. This involves the negotiation of a number of separate and complex construction contracts.

That number can be anywhere from two to several hundred, depending on how much integration is done at the project level. Utilities will often go for a fairly large number of contracts that they manage in–house through their experienced procurement and project management teams; debt financed projects will typically have only a handful of contracts as banks are not willing to let developers take the project management risk over a large number of contracts. It also requires the negotiation of complex funding documents for equity and debt. Those documents require the preparation of a number of due diligence reports by external experts, typically for technical matters, legal review, tax, accounting and insurance issues.

To some extent, this phase can be done in parallel with the previous one, but most counterparties (contractors, investors, lenders) will want to see a project with a high likelihood of being built before they commit negotiation teams and commercial resources. Contractors and lenders will be willing to work with a project that has a permit under appeal if the appeals process is well understood and has a clear maximum period to be settled, or that needs to complete certain studies (also if they are well defined, or cover a pre-agreed period), or where certain regulatory approvals are only provided at a later stage (for instance, in Germany, where the irrevocable commitment by the grid operator to set up a connection to the wind farm is subject to certain construction contracts being signed and financing being in place). But a project still in early stages of permitting, or stuck in unpredictable appeals procedures, or going through that process for the first time in a country, will probably fail to attract the attention of counterparties and will not be able to begin detailed negotiations until fully permitted, let alone receive binding commitments.

Small developers can try to negotiate the construction contracts on their own and then raise equity, and then debt, to fund the project as they have designed it. This has been done successfully by a small number of projects (such as Gemini, Nordergründe and Veja Mate) but there are also a substantial number of developers who have tried this route and failed (examples include MEG1 – as will be described in a later section – Cape Wind, or Nordergründe and Veja Mate with their previous owners). The alternative is to bring in new investors prior to negotiating the commercial and financial structure, but such transactions typically involve investors that are keen to take charge of these processes altogether, with the original developer keeping a minority stake only (or a milestone-based success fee) and having little influence on the rest of the development. As a result, developers who wish to retain full ownership and control over a project will have to provide their own equity funding.

The development phase ends at “financial close” (FC) for projects with non recourse debt (or “levered” transactions) or “final investment decision” (FID) in the case of projects without non recourse debt (or “unlevered” transactions). At that point in time, all construction contracts are signed and effective (i.e. all conditions precedent to their effectiveness have been fulfilled), the financing is signed and irrevocably committed, and construction can start.

This last part of the development phase will typically require spending something in the range of 0.05‑0.1 MEUR/MW for overall negotiations for a utility–scale project (mainly in advisor fees, some of which can be delayed to financial close) but may require substantially higher commitments from the sponsors if certain long lead items need to be ordered in advance so as to stick to the proposed timetable. For instance, down-payments to order steel, or cable manufacturing, are often required long before financial close. The alternative is to make these orders at financial close only but have the overall construction schedule delayed by a number of months since even a short delay in the availability of foundations or cables can cause the project to miss those available installation windows either because of the weather (most installation activity takes place in the summer when work conditions in the water are easier) or regulatory constraints (limitations on construction activities linked to migratory patterns, nesting periods, or fish spawning areas, for instance).

- Main risks

- Changes in regulatory framework that make the project unviable;

- Inability to negotiate the construction contracts;

- Inability to raise the equity for the full development costs;

- Inability to raise equity and debt for construction.

- Timing and funding required

- Several years;

- 10‑0.15 MEUR/MW for pure development expenses (including early development costs), and up to an additional 0.1 MEUR/MW in commitments for long lead items.

In the next instalment (Part 6) we will look at construction and operation phases and the profile of investors.